Ringing in the new year is always a time for reflection and prognostication. That's no different at JVM Studio, but we'll keep things short and sweet.

Read MoreHow should cities respond to Uber and Lyft? The Philadelphia Inquirer asks JVM Studio to weigh in

Researchers from the University of California-Davis Institute of Transportation Studies just completed one of the most comprehensive studies to date on how people use ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft. The Philadelphia Inquirer asked four local experts - Chris Puchalsky from the City of Philadelphia, Erick Guerra from the University of Pennsylvania, Brett Fusco from the Delaware Vally Regional Planning Commission, and JVM Studio's Jonas Maciunas - what the study's findings mean for Philadelphia.

Read MoreFeatured in PlanPhilly

Last year, PlanPhilly asked people why Philadelphia needs safer streets. Here's what we told them.

Measuring The Street: Cars in the Italian Market

Parking is essential to retail, right? Especially in off-center commercial corridors with a reputation for attracting tourists and folks coming back to "the old neighborhood," right? Philadelphia's iconic Italian Market is on its way to establishing a business improvement district, giving the district the capacity to make some collective decisions. Janette Sadik-Khan, New York City's transformative former Transportation Commissioner under Michael Bloomberg says that measuring the street for transportation, economic, and social impacts of design changes is critical to good decision-making. I thought I'd test the thesis of the importance of parking and car access by doing some simple counts on a busy Saturday. What I found was pretty surprising.

Read MoreEast Market Street Requires a ReDesign

East Market Street was designed in 1984 and no longer serves the needs of our city or the preferences of the market. Not only does it create an unsafe pedestrian environment, constraining the economic potential of the district, but it provides no enduring pleasure. Philadelphia’s “main street” should be a joy to stroll along. Amid the ongoing surge of private investment, the time has come to take a hard look at the priorities of the public realm on East Market Street.

Read More(Accidental) Success for OpenStreets PHL

Open Streets, the national effort to open up streets to pedestrians, is gaining steam. Millennials love it; it makes children happy, and it even seems to give old folks an extra spring in their step. But what about entrepreneurs and mom+pop retailers trying to make a buck? Might such restriction of vehicular traffic and parking dissuade their customers, squeeze their margins, and be more of a headache than it's worth? We got a chance to find out, and the results were really exciting.

Read MoreTransect Talk: Trails and Parkland

Philadelphia has a beautiful history and network of parks and trails. After a long hike a little while ago, it dawned on me that parks and trails, just like buildings and streets, range from urban to rural, and that "getting it right" in those various contexts makes a huge difference. In other words, beaux-arts fountains in the woods make about as little sense as building a raised ranch with a picket fence next to City Hall. I'm going to use this post to show how a great long hike through Philadelphia parkland exposes you to a nearly perfect transition through the trail transect.

Read MoreHalloween: another reason row houses are totally awesome

Halloween might be the holiday made best by walkable urban places. Christmas and its caroling has its charms and may give All Hallows Eve a run for its money, but who can argue the awesomeness of trick-or-treating with a new door to knock on every 15-to-100 feet? I can't imagine being a kid in the exurbs. Being driven around to each and every daily activity is bad enough, but imagine needing to be driven house to house for trick-or-treating? Fortunately, the town I grew up in was an inner ring suburb well built for halloween. Even so, I've been blown away by the spooky atmosphere created in my Philadelphia neighborhood. People really go all out, and the proximity to the sidewalk of each Halloween-costumed house really heightens the experience.

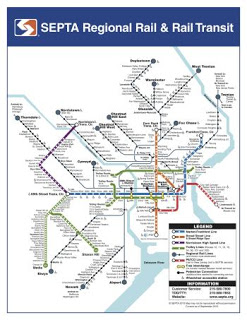

Read MoreSEPTA Expansion: First, How Did We Get Here?

Since then, however, the passage of Act 89 by the Pennsylvania legislature, in the words of the General Manager, "is a watershed moment for transportation in the Commonwealth. For the very first time, transportation agencies have a predictable, bondable, and inflation-indexed funding solution to to repair failing bridges, highways, and transit systems across the state. Already, credit rating agencies foresee a positive economic outlook. The entire state stands to benefit from this landmark piece of legislation.

"For SEPTA, Act 89 provides an opportunity to play catch up on a growing $5 billion backlog of capital replacement needs. The funding will allow SEPTA to advance a wide-ranging program of mission critical projects, such as bridge replacements, substation overhauls, and and the customer experience."

What does all that mean? Basically, in addition to improved customer service, other management practices, and the long-awaited deployment of new payment technology, there will be a lot going on behind the scenes (and under the bridges) to get the existing system up to snuff and still functioning ten years from now. In other words, $5B for critical things that will, in many ways, go unnoticed and, unfortunately, might not be broadly appreciated.

One exception is going to be the replacement of the 1980 trolley fleet with new, low-floor boarding, higher capacity vehicles. THIS will be a transformative investment, especially for West Philadelphia, where what basically operates as a system of buses that can't get out of the way of an obstruction in the street, will be transformed into a modernized system that functions more like the light rail we're always finding ourselves jealous of in far-flung places like Portland and Houston. Faster boarding, greater vehicle capacity, and stations that extend the sidewalk out to the track will be like a brand new rapid transit system for West Philadelphia. This a big deal, and with a little luck (though limited confidence, given the recent track record), SEPTA will avoid the siren song of advertising/sponsorship, and develop/keep a strong visual brand for the newly improved system... but more on that another time.

But this all still begs the question: what's next? SEPTA has a predictable revenue stream in place for the first time ever. It's prudent to make these state-of-good repair and service improvements first, but before long, they will have been made, and we'll still have this revenue stream in place. We shouldn't be proposing any major service expansions until the system is restored, but once it is, the legislature could easily cut that funding stream if additional transportation needs of the region aren't being planned to be met.

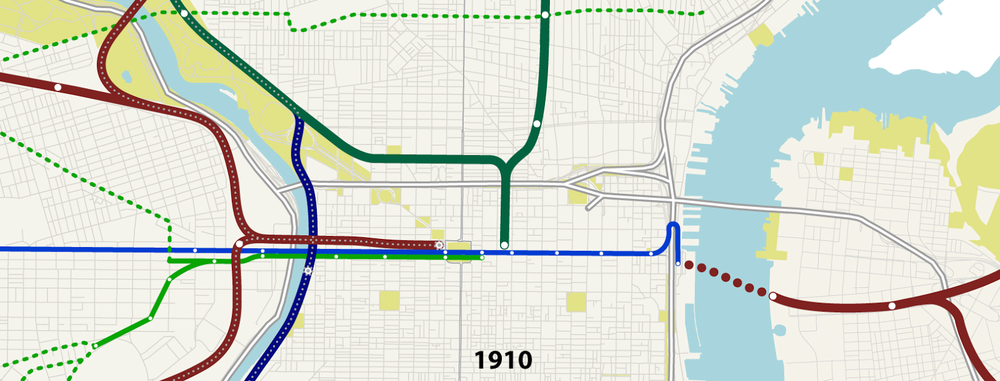

There will be plenty of time to speculate about service expansions - new subways, regional rail re-extension to places like Reading and Lancaster, trolley restoration, rapid transit on the Boulevard, and more. But right now, I thought it'd be good to illustrate the building of the Center City passenger rail network over the years. After all, it was built incrementally, not over night, and any future changes should stand on the shoulders of the evolution of the system before them. These maps are based on a my synthesis of historic maps of the city and some cursory, non-academic research (wikipedia and some rail fan sites) on operators and stations. Other than the ones that still exist today, I avoided showing trolleys (which is a whole 'nother discussion of disinvestment, repeated city after city). This is not meant to be an exhaustive review of each and every detail, and I'm sure there are corrections to make, but the intent is to show the general trajectory we have been on, in order to better consider where we'll go next.

The Early System

In the earliest days, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran trains all the way down Market Street to the Delaware River by way of Dock Street. But after we realized you really shouldn't be running steam locomotives down you Main Street, here is what we got. The Reading Railroad, naturally, terminated at Reading Terminal and the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated at the grand Broad Street Station, both built in 1893. It's worth noting that until 30th Street Station was built, and Broad Street was demolished, intercity trains (think today's Amtrak service) would pull all the way into Broad Street, across the street from city hall, and then back out to continue their journey.

There was no subway or 30th Street Station, just a smaller station at 32nd Street. The Baltimore and Ohio ran a line along the Schuylkill, with a pretty beautiful station at Chestnut Street, and service to New York City that didn't require the Broad Street back-in-and-out. West Philadelphia trolleys converged on Market Street and ran all the way to Front Street, where they looped around. The Pennsylvania Railroad also ran a New Jersey based division that terminated at Camden (these trains went north and to the shore). Ferry service between the cities abounded. Remember, unlike today's Monolithic SEPTA (with the exception of PATCO and NJTransit buses) this is in the era when services were run by lots of different operators. I won't be getting into the details of which is which, generally, but it's worth remembering.

Subways on Market Street

Rapid Expansion

The 1920s and 30s witnessed huge expansion of the system. Let's look at what those expansions were.

- The Frankford line opened in 1922. For a brief period, the Market Street subway would have two branches - the Ferry and Frankford lines.

- The Broad Street line opened in 1928, but terminated at Lombard/South.

- In 1932, the Broad Ridge Spur began service from the north to 8th and Market Streets.

- The Pennsylvania Railroad opened Suburban Station in 1930 and 30th Street Station in 1933, intending to send intercity trains through 30th Street and suburban ones underground (I do love the station's double-meaning) through Suburban. The Broad Street Station remained, however, presumably because money had run out to tear it down, and continued to serve a portion of the city's intercity service until it was torn down in 1952.

- in 1936 (yes, i know, a year after the image is labeled), the Delaware River Joint Commission (predecessor to PATCO) began running the "Bridge Line" on the newly constructed Ben Franklin Bridge. This would spell trouble for the ferries. Originally, this line only ran between Broadway in Camden and 8th and Market Streets in Philadelphia. Connections to the Pennsylvania Railroad were required for any journeys east of Camden from Philadelphia.

Mid-Century Retrenchment

With the construction of highways sweeping the nation, you wouldn't think there would be much happening on the railroad front. In fact, retrenchment was the spirit of the era.

- In 1952, the Pennsylvania Railroad demolished Broad Street Station, formalizing the condition we know today (with one major exception) where regional trains run to suburban, and intercity trains run to 30th Street.

- The B&O Station at 24th and Chestnut was closed in 1958.

- After a some temporary closure, the Ferry Line of the Market Street subway was closed in 1953. This eventually makes way for Delaware Avenue and I-95.

- There is a general demise of regular ferry service across the Delaware,

- The Broad Street line had been extended south of Lombard/South to Snyder Avenue in 1938.

- Most notably, the Delaware River Port Authority was created in 1951, taking over the Bridge Line. Hired by the Authority to develop a rapid transit plan for South Jersey, Parsons Brinckerhoff recommended building a tunnel to serve three lines. Though the tunnel was deemed to expensive and eastern improvements wouldn't happen yet, the line was extended in Philadelphia to the Locusts Street terminus we know today.

More Stagnation, but stabilization in a Chaotic Era

Despite Ed Bacon's fantasies of miniature trolleys shuttling people back and forth on Chestnut Street, the 1960s were still all about highway construction. However, this period also witnessed the implosion of the private passenger railroads. Everything got really confusing and entities like SEPTA were created to manage the chaos. In 1968, PATCO began running one the three lines PB had recommended into Center City by way of the Ben Franklin Bridge. Though SEPTA didn't own track and rolling stock until 1983, by 1966, both the Reading and Pennsylvania Railroads operated commuter lines under contract to the Authority. This set up the situation where the SEPTA regional rail system was bifurcated between trains terminating at Suburban and those terminating at Reading. Enter: Vukan Vuchic.

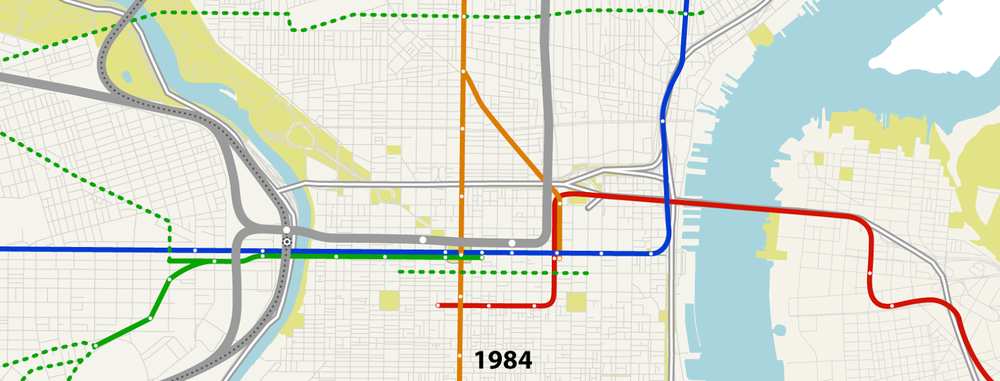

A Breakthrough Moment

The construction of I-95 on the Delaware River shifted the El from Front Street into the highway alignment we know today, and replaced a Fairmount station with today's Spring Garden Station. Ed Bacon's vision for Chestnut Street was tranformed into The Transitway in 1976, though it would be incrementally dismantled. Most importantly, the Center City Commuter Connection created a tunnel between Suburban Station and Reading Terminal, renamed Market East (and now, Jefferson Station). This connection allowed for trains that used to terminate at each station to pass through Center City to become another route on the other side. Though SEPTA has been criticized for not sufficiently taking advantage of the connectivity the tunnel allows, as I've discussed before, doubling the transit access to Market West is indelibly linked to its growth as an office district.

Today - The Lull Before the What?

Since the Tunnel's completion in 1984, however, little has changed in the system, with the exception of the creation of the River Line between Camden and Trenton on the other side of the Delaware. In Philadelphia, the broader retrenchment trend of the second half of the 20th century continued with the gradual elimination of the Chestnut Street Transitway and the 1992 replacement of Route 23, 15, and 57 trolleys with buses (though the 15 on Girard Avenue would be re-instated in the next decade).

It's been a long time since any major network changes have happened in the central Philadelphia transit system, mostly because SEPTA has been doing its best just to minimize the bleeding. But now that the Authority is in a strong financial position for the foreseeable future and is making lots of state-of-good-repair improvements (and majorly re-investing in the existing trolley system), the question should be asked: what's next?

There will be plenty of time to thinking and discuss that, but a good place to start is to look at where we've been.

When a Bike Lane is More than a Bike Lane

|

| Philly PD, in the bike lane and ON the sidewalk. I have dozens of such photos. |

|

| Protected bike lanes are safer for all users. (photo: US Dept. of Transportation) |

|

| Keep the tickets coming! |

Think tank’s urban jobs agenda misguided: cities must be empowered, not wards of the state

Make Transit a Downtown Priority and Get the Details Right

Introduction

|

| Acres of parking in the shadow of tens of thousands of jobs and the State Capitol |

A big part of the solution is improved transit, and with fewer than 10 percent of downtown Hartford employees currently using transit, there’s room for improvement.

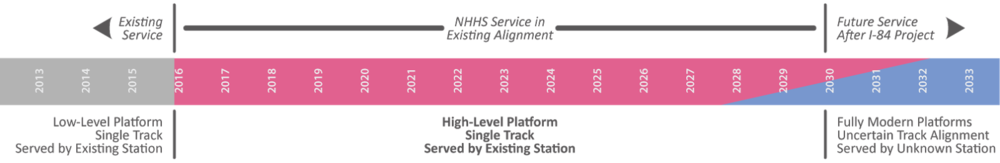

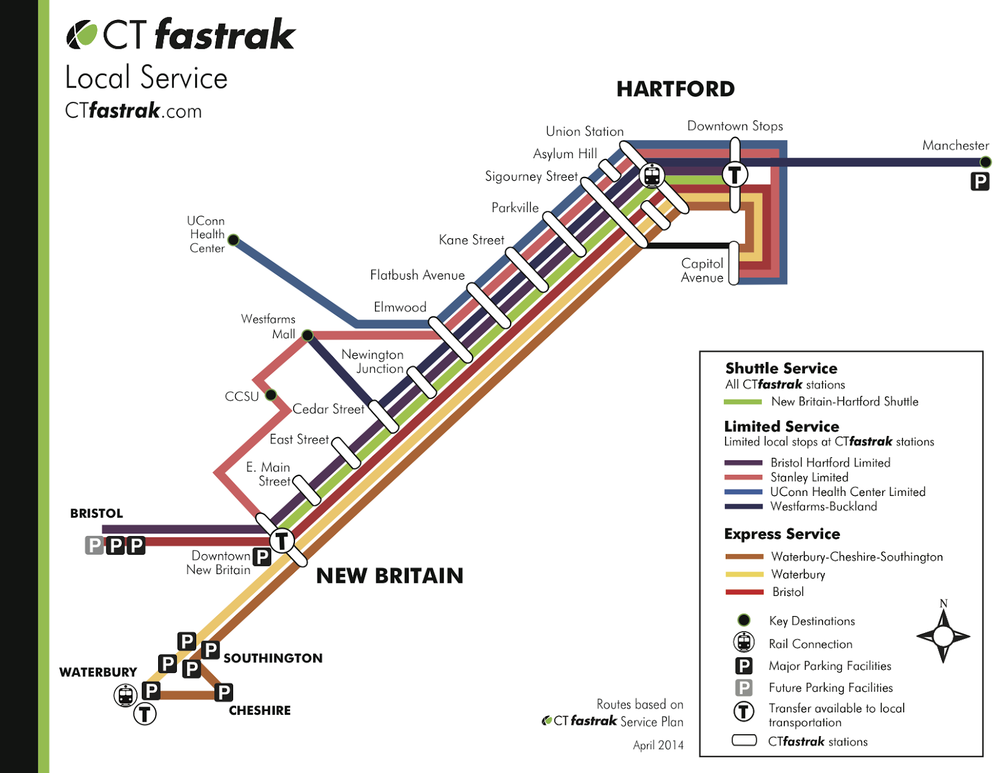

The current bus system, while imperfect, is fairly robust, and in 2015, CTfastrak will create a fast and reliable car-free option from New Britain to Hartford, serving points in between and beyond. In 2016, the state Department of Transportation’s implementation of the New Haven Hartford Springfield rail program will triple service to Union Station. This is a big deal.

|

| CTfastrak local service map (www.ctfastrak.com) |

|

| New Haven-Hartford-Springfield service map (www.nhhsrail.com) |

However, just as the best retailers know that offering good products and being near foot traffic aren’t always enough, maximizing transit ridership is about more than building the infrastructure. It’s about enhancing the convenience of the service so current passengers get the most out of it and newcomers want to try it.

If they miss this point, the new Hartford bus and rail services will sell themselves short.

Union Station

|

| Streetscape improvements designed for Union Place (Tai Soo Kim Architects). Construction beginning in Spring 2014 |

In anticipation of other forthcoming improvements, the Hartford Business improvement District, together with the City and the Transit District, has added new signage to Union Station, providing orientation and helping to better position the Station toward Asylum Street.

|

| Asylum Street for St. Patrick's Day Parade (ctnow.com) |

|

| Union Station Transportation Center, next to the Great Hall |

|

| Union Station's Great Hall begs to be put back to use as a transportation hub |

|

| A ConnDOT rendering of the elevated platform (right) illustrating how it is accessed |

|

| A section of the platform improvements by the Connecticut Department of Transportation |

| An elevation of the platform improvements by the Connecticut Department of Transportation |

At the end of the day, this looks like a bare-bones effort to meet the minimum standards of the American's with Disabilities Act (ADA), not to create a first-rate travel experience for all users or anticipate exceeded ridership projections. However, the department is unwilling to consider bolder alternatives because of possible track relocation related to the transformative reconstruction of I-84. According to Commissioner Redeker, those changes are almost 20 years away.

|

| Big-Time changes to the face of Downtown Hartford if I-84 is rebuilt and the railroad is shifted (credit - Tri-State Transportation Campaign) |

Two blocks east, the governor has announced funding for over $30 million of hospitality-oriented improvements to the XL Center “to get eight to ten years out of it, frankly.” Union Station merits similar consideration.

|

| A section of an alternative platform improvement |

| A section of an alternative platform improvement |

|

| A basic 3-D model, showing the Great Hall (right), existing station-adjacent platform (right-center), multiple stairs and ramps (left-center), and an elevated platform over the un-used track area. |

CTfastrak and Local Bus Service

|

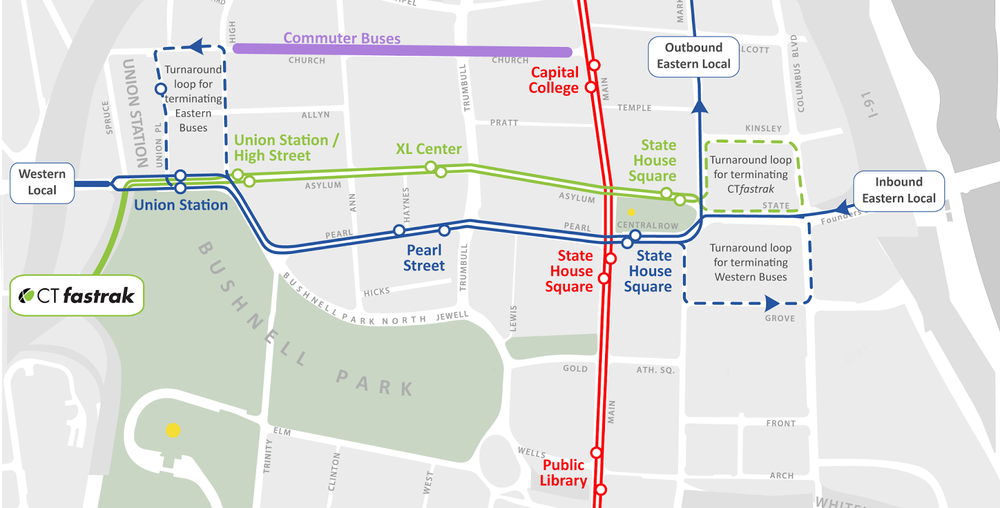

| Transit Routing Today in Downtown Hartford |

The City was awarded a federal grant (the TIGER-Funded Intermodal Triangle) two years ago to improve the pedestrian experience from Union Station to Main Street and make changes to bus routing to improve service and maximize the impact of CTfastrak. In 2012, city, state and regional transportation officials determined that reopening the historic “isle of safety” at the Old State House and utilizing Pearl and Asylum Streets could create direct, convenient downtown access and ease pressure on Main Street.

|

| Transit Routing as Planned by the City of Hartford, Capital Region Council of Governments, and Connecticut Department of Transportation in 2012 |

|

| Bus lane on Chestnut St. in Philly |

As a result, Farmington Avenue buses from the west will become less convenient to the heart of Downtown, Pearl Street will continue to be used as a parking lot by commuter buses, CTfastrak won’t directly serve the XL Center, and Main Street will have even more buses than today, with the addition of western routes terminate on the block just north of Asylum Street. With CTfastrak expected to replant the stops of today's western routes, one must conclude that northbound routes will continue to stop in front of the Atheneum and Old State House.

A city aspiring to be transit-oriented needs to make destinations convenient to get to and not let its transportation undermine its placemaking efforts.

|

| Transit Routing as Inferred to be Planned by the Connecticut Department of Transportation |

|

| An Alternative Transit Routing Among Many |

Conclusion

Whether at Union Station or on downtown streets, improved transit is one piece of the puzzle to make Hartford more livable, accessible and development-oriented. But transit will only flourish if the city and state work with the community to make it a priority and realize a vision in which parking is no longer the best use of prime downtown land. We still have that opportunity; let’s get it right.

Economic Development - How Philadelphia Snagged Comcast without Giving Away the Farm

|

| The tall building is the original Comcast Center; the taller building is the Innovation & Technology Center (courtesy of Comcast) |

|

| Rendering of Jackson Labs in Farmington (www.governor.ct.gov) |

|

| (courtesy of planphilly.com) |

|

| Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts (courtesy of phillyfoodfinders) |

Center City Living. Speaking of growing residential population, Center City Philadelphia's rose by 16% between 2000 and 2010 to over 57,000 people, leading to the first overall increase in the city's total population in over sixty years. And it's no longer a secret that a thriving residential population is key to any downtown revival, and that the option of downtown housing is appealing to many working for companies that cities around the country want to attract. But this population rise wasn't an accident either. In 1997, the City of Philadelphia boldly enacted a 10-year tax abatement program, triggering genuine boom in downtown residence. Though controversial, that's a tax incentive almost anybody can take advantage of, and by most accounts, it has really paid off.

Philadelphia has always been a walkable city with unbeatable historical assets but those things wouldn't have led to the development of the Comcast Center without improvements to transit, placemaking, and center city living. This trio is certainly not the whole nor the end of the story, but it is a case study in strategic moves made to encourage growth. Each of these improvements require a city's investment in itself, and none of them come cheap. They also don't provide the instant gratification of job creation, but such is the nature of patience.

The difference between this sort of strategy for recruitment of companies and the jobs that come with them, and one built on specific financial incentives in each "economic development" deal, is that they benefit everybody and can be taken advantage of again and again, in a virtuous cycle. If I were so bold, I might even call that sort of economic development "sustainable."

Other cities, take note.

The Unnecessary SEPTA Doomsday Scenario

Some will suggest that transit is a drain on tax money that should operate more like a business (or that it should even be private business), despite not holding roads and highways to this same standard. But let's looks at SEPTA's operating and capital circumstances.

Here's the amazing thing: based on data from the National Transit Database, SEPTA (2011) has the third highest operating recover ratio (revenues from fares per operating costs) of any commuter rail service in the country - 56.7% - all while while offering service remarkably cheaply the average ticket costs only $3.60... meaning each ticket's operating subsidy is only $2.70. You don't get much lower than that, so suffice it to say that on the business-efficiency argument, SEPTA scores mighty high marks. One would think that such high performance would ought to be rewarded, not forced into doomsday cuts.

That's the operating side. But on the other capital side, SEPTA is basically funded by farebox returns and the general fund of the state, for which it is always competing with every other worthy and unworthy interest in government. How can you expect a capital intensive activity like transportation to operate "like a business," without having any real capacity for capital investment? The result is that the agency is doomed to fail through deferred maintenance.

Some more enlightened regions have come up with alternatives. New York's MTA uses bridge/tunnel tolls to to help pay for transit (which then mitigates congestion by giving people non-bridge/tunnel options). Denver and Los Angeles have what amount to special assessment districts that fund transit. Even Houston, in that lone star land of fiscal conservatives, has 1% sales tax dedicated to transit. There are many ways to skin this cat and give a transit agency borrowing capacity it needs to perform critical maintenance and service expansions.

At the moment, it's important for the legislature (pushed by the City and counties with potential service cuts) to pony for capital improvements. But until Pennsylvania comes up with a means of providing SEPTA with capital funding that doesn't depend on the Commonwealths general fund budget, these doomsday scenarios will inch toward reality, and we can forget about any kind of future service expansions.

ThirdPlace WorkSpace: Special Edition - Park(ing) Day Preview and Recommendations

|

| Park(ing) Day example from StreetsBlog |

|

| Philly Parklet in Chinatown (from MOTU) |

|

| From Data Driven Detroit |

Parking can be important, especially for retail, so maybe a prudent approach, in places that aren't fully built out, would be to focus Park(ing) day activity, not just on on-street spaces, but strategically problematic surface parking lots.

Find the lot that you really think should be a building, rent the corner or edge spaces for the day, and set up a lemonade stand (even if you give it away for free in order to avoid the ire of the relevant city department) or something as a means of simulating the commerce that should be taking place there and helping others visualize it.

In Portland (Oregon, this time, though it pains me to admit), the foodcart vendors that we all know and love are begining to more permanently occupy edge spaces of parking lots and other unbuilt properties. This demonstrates an incremental approach to development and improvement of the public realm that doesn't depend on big, overnight change, which can be so hard to come by.

|

| from planningpool.com |

|

| from eatingmywaythruportland.com |

ThirdPlace WorkSpace Thursdays: Ultimo Coffee Bar

It's a small space (probably 15 feet deep and 45 feet wide), so it stays intimate, which is always good. table-wise, they've picked a table and stuck with it the whole way - square and comfortable for one person with a laptop or two people without computers. Being on the corner, the shop has a lot of outdoor exposure to work with, which they've maximized by having glass sliding doors across the whole thing (which I've not acdtually seen open, but they make for great natural light). Outdoor seating also exists on the other side of those doors, which is nice. The look inside is simple and natural - a fair amount of wood paneling and elegantly hung single light bulbs. Tunes playing over the speakers are always pretty good - anything from Carla Thomas and Eddie Floyd to The Clash and The Smiths.

Food and beverage wise, you really can't go wrong. The coffee is flavorful, wonderfully prepared, and never bitter, and the milk comes straight from Lancaster, they way it should always be. Bagels, croissants, etc are good, and they carry sandwiches pre-packaged by Federal Street's own American Sardine Bar.

Philadelphia seems to have a bunch of good cafes with a few locations. I'm definitely going to have to check out the original Ultimo now. Stay tuned.

www.ultimocoffee.com

22nd & Catherine Streets, Graduate Hospital

Table Space – two-seaters, ideal for laptop or a two-person meeting

Third places in a city or town are those that are neither home, work, nor shopping… they are the informal places in between, the public living rooms where we gather or go to be alone in a crowd… and there’s good argument that a culture of solid third places (Parisian café culture is so good as to become cliché) is a driver and indicator of community vitality. They can also be great workspaces for those of us not wanting to work from home, not yet being ready to pay for “real” commercial space, looking to get out of the office, or have a more informal meeting. There’s etiquette (called buying things and not being a slob with your belongings) to working in a café, but doing so can be good for you and the proprietor alike. In this blog, I’ll take you on a reviewed tour of some of Philadelphia’s ThirdPlace WorkSpace (trademark pending) opportunities. I hope you join me.

Naked Bike Ride... Effective Tactical Urbanism or a Robespierre for a Bicycle Revolution?

ThirdPlace WorkSpace Thursdays: Wi-fi and Learning from Starbucks

Last week in the Atlantic Wire, Alexander Abad-Santos reported on some coffee shops banning the use of laptops, while starbucks is taking advantage and trying to attract people by partnering with Google to vastly speed up their wi-fi. On one level the visceral response too prohibit "moochers" by mom-and-pop coffee shops is understandable... they've got limited space and somebody working on a laptop might not be spending as much per space-time occupied as somebody else. At the same time, well... Starbucks is no dummy. They're not luring people with wi-fi because its going to be a money loser for them. As urban retail expert Bob Gibbs has frequently pointed out, malls learned a lot from traditional urban retail streets, which can, in turn, learn an awful lot from the way malls are designed and managed. I would say that same might be true for coffee shops.

Different cafes of different sizes in different neighborhoods cater to different clientele. Some churn out cups-o-joe for the working stiff on their way to the office; some focus on their baked goods and sandwiches; others fancy themselves as neighborhood lounges. Much of that depends on location (being in the heart of an office district is much more likely to make you a cup-churner than a hangout-for example). Design of the space inside also plays a role in shaping the activity and business a cafe will make. Couches or chairs with very small table tops tend to not make for good long-term laptop squatting. Multi-person tables, especially when there's no single-seat option, run the risk of being monopolized by a rude laptop user (I'm a firm believer that, other than in the least busy cafes, a laptop user shouldn't act as though its their right to spread out over space that others could be using). I suspect it's the busiest cafes that struggle with the presence of laptops the most (because unless you're full, the use of space can't really negatively affect you). If that's a majority of business in a fully shop, you might even build it into the cost of a cup of coffee.

So for the sake of us patrons and resistance to

Third places in a city or town are those that are neither home, work, nor shopping… they are the informal places in between, the public living rooms where we gather or go to be alone in a crowd… and there’s good argument that a culture of solid third places (Parisian café culture is so good as to become cliché) is a driver and indicator of community vitality. They can also be great workspaces for those of us not wanting to work from home, not yet being ready to pay for “real” commercial space, looking to get out of the office, or have a more informal meeting. There’s etiquette (called buying things and not being a slob with your belongings) to working in a café, but doing so can be good for you and the proprietor alike. In this blog, I’ll take you on a reviewed tour of some of Philadelphia’s ThirdPlace WorkSpace (trademark pending) opportunities. I hope you join me.

Thinking about Snow in August: A Fiscal Case for Walkable Development

Today, StreetsBlog featured an article about how fire departments both perpetuate and are victimized by sprawl. The premise basically being that the requirements for streets to accomodate the department's largest fire engine begets wider streets and perpetuates the vicious cycles of sprawl sprawl inducement. In turn, they speculate that volunteering to be fire fighter becomes harder, since so much time in a car-dependent place, is dedicated to driving. Mark Abraham over @urbandata posed it a different way, asking, "if we did away with #sprawl, what could the typical firefighter salary be increased to?" This reminded me of some very tangible fiscal benefits to compact, walkable development I noticed during last year's big snow storm.

|

| From Alan Chaniewski of the Hartford Courant |

In the middle of February, central Connecticut got about three feet of snow nearly overnight. Major avenues were brought to a near standstill for hours, and plenty of neighborhoods didn't dig out for several days. Walking through my neighborhood, I watched people shoveling out their sidewalks and driveways, simultaneously waiting for and dreading the moment when the city plow truck would come by and undo much of their hard work.

As a homeowner, would you rather shovel 20 feet of sidewalk or a hundred feet? That's the difference between a row house and a fairly typical detached single family house. Given the responsibility, I would certainly choose the row house (or better yet, the 20-unit apartment building with only fifty feet of frontage).

By the same token, cities must deal with plowing the streets after such an event. Let's imagine a block of a residential street is 500 feet long. Either way, the city needs to plow it. For the sake of argument, let's say that costs $100. If the street consists of the aforementioned detached homes, there would be about ten of them (five on each side) per block, costing each household ten bucks to plow the street. The same street, consisting of row houses would divide the cost by fifty... rendering a plowing cost of only two dollars per household. Which place would you rather be a tax-payer in?

The same back-of-the-napkin analysis can be done for many a public service or utility... water distribution, transit service, electrical lines, etc... and I would contend that it'd hold true for fire departments too. It's also probably not too bold to suggest that, all other things being equal (and no, they usually aren't), a more densely populated place can afford to pay its employees more than a less densely populated place, while still being a relative bargain for taxpayers.

The economic efficiency of density isn't a new concept, but in light of the continuing great recession and the squeeze on municipal and state budgets, highlighted by the bankruptcy of Detroit (and no, your city is probably NOT the next Detroit, but that's another story for another time), I'd say it's high time we start thinking more about the fiscal benefit of walkable places.

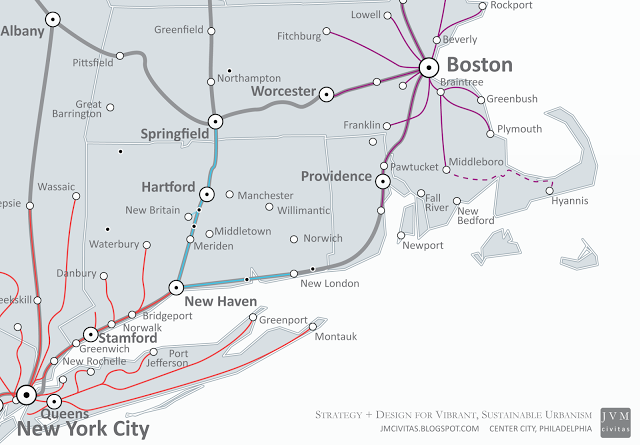

Beyond Springfield: Reconnecting Central New England with the "Inland Route"

Governor Patrick recently (and rather quickly) reinstated weekend service from Boston to Cape Cod after 25-year dormancy (see the dotted line below). As the Berkshire Eagle reports, he'd also like to see the Housatonic railroad restore service to Pittsfield for the first time since 1971. Like the Cape, the Berkshires would almost certainly benefit from increased tourism opportunities from New York, and depending on the service, commuting from Great Barrington to Norwalk or Stamford, for example, could become possible. But since much of the inactive route north of Danbury is in Connecticut, he needs the Nutmeg State's help to do it. I'll come back to this in a bit.

|

| Today: Intercity and Commuter Rail (including CT's forthcoming projects) |

However, as Kip Bergstrom, Connecticut's Deputy Commissioner for Economic Development, has frequently pointed out, Connecticut's, especially Hartford's, opportunity is not necessarily in connecting New Haven to Springfield, but by transforming itself from being the edge of the New York or Boston metropolitan areas to their center. He says passenger rail (probably an intermediate between commuter and intercity) is the tool to make this happen, which is why it's so important that the New Haven - Springfield route is being upgraded and service is being restored. Unfortunately, today and as currently planned, the vast majority of southbound trains terminate at New Haven and require a connection to MetroNorth or Amtrak (of which there are several options), and other than one Amtrak train to Vermont, northbound trains not terminating in Hartford (five of them will) will terminate in Springfield, with no meaningful connections to Boston.

|

| from NEC Future (preliminary alternative 14) |

A prudent and achievable approach, which ConnDOT mentions in general as part of a broader vision, would be to focus on connections between central New England and Boston, be restoring service to what was known as the "Inland Route." Despite usually requiring connections at New Haven (a one-seat ride would certainly be preferred), there are countless southbound options to New York, and other than some possible MetroNorth extensions to Hartford or Springfield, additional service won't be feasible until additional track space is somehow created south of New Haven.

At the very least, New Haven-Hartford-Springfield service should become New Haven-Hartford-Springfield-Worcester Service. There are seventeen recently added daily MBTA trains from Worcester to Boston (which have been a huge boon to the city of Worcester), any number of which could be integrated into this expanded Inland Route service. Even if full New Haven-Hartford-Springfield-Worcester-Boston service isn't possible due to track or schedule capacity, the connection options are still available at Worcester.

|

| Possible Improvements: Berkshire Service to Fairfield County and NYC; Revival of the Inland Route between New Haven and Boston |

If Massachusetts needs Connecticut's help to restore Housatonic service from New York City and Danbury to the Berkshires, Massachusetts ought to do its part for Connecticut by helping restore real service between Springfield and Worcester. Northwestern CT communities like New Milford and North Canaan would certainly benefit from the former, and Springfield would absolutely benefit from the latter, not to mention all those Bostonians looking to get to its new casino or make use of increased access to points south. This will require the Commonwealth - and quite possibly the Congress - to work with CSX, the owner of the Boston-Springfield rail, but the fate of central New England depends on it.

In 1999, Amtrak upgraded infrastructure (electrification between New Haven and Boston, along the coast) and introduced Acela service. As a result, speeds increased and service jumped from eleven to nineteen daily trains (based on Amtrak timetables) in each direction between Boston and New Haven; this improvement led to a 45% increase in ridership in 2000 (revenue up by 77%), alone. The City became better integrated with the rest of the Northeast Corridor and has certainly continued to reap the benefits. This phenomenon can happen for the Central New England cities of the Inland Route, and be repeated in Boston with restoration of continuous service along New Haven-Hartford-Springfield-Worcester-Boston.

Cities with good passenger rail service will attract people and reap the economic benefits, and those without will likely not. But in a dense region of small jurisdictions like New England which is often slow to change, such service will require consensus and hand-in-hand collaboration, with a touch of impatience, of the of all elected, appointed, and private sector leadership.