When Jan Gehl was in Philadelphia in February to accept the 2016 Edmund N. Bacon Prize, he took a walk down Market Street with PlanPhilly's Ashley Hahn. There's many a gem in her recap of their walking conversation, but overall, Gehl concludes that while there are glimmers of "vitality and variety" in Old City, the core of East Market Street is a loveless experience. In many ways the street is designed to keep people (especially in their cars) moving, instead of basking in the pleasant urbanity of it all.

Ashley asked me to write a companion piece to her conversation with Gehl, about the challenges and opportunities facing East Market Street. This post originally appeared in PlanPhilly. Supplemental graphics and text (captions and italics) are intended to lend further clarity and depth to the issues presented in the original text.

A Brief History of Change

East Market Street is Philadelphia’s historic shopping district. Its east end was the city’s original port. It carried the earliest iterations of the Pennsylvania Railroad to market sheds on its center line. Philadelphia’s great department stores were born and expanded on it. Midcentury urban renewal created the iconic Gallery on its north side.

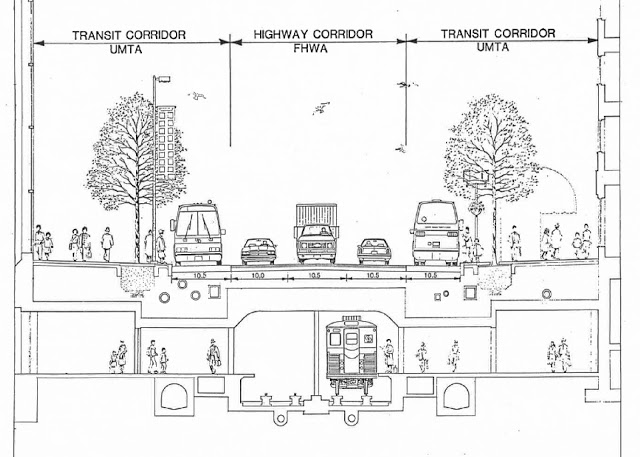

Over the course of these same generations, the physical character and organization of East Market Street itself shifted dramatically to respond to changing technology, trends, and preferences. As the 20th Century wore on, the wide sidewalks of the early department store era were narrowed to accommodate more vehicular traffic and trolley riders were moved onto floating islands in the street. Following construction of the Gallery, the Urban Mass Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration funded a reconstruction of the street in 1984, leading to the form we recognize today – re-widened sidewalks, a “highway corridor”, and a “transit corridor.”

The 500 Block of Market Street in the, probably in the 1880s. In the 1860s, Market Street (originally called High Street) was largely unpaved and carried the freight trains of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Market Sheds in the middle of the street (akin to the headhouse market on 2nd Street in Society Hill) later accepted goods from freight trolleys and served the community. (image credit: Free Library of Philadelphia)

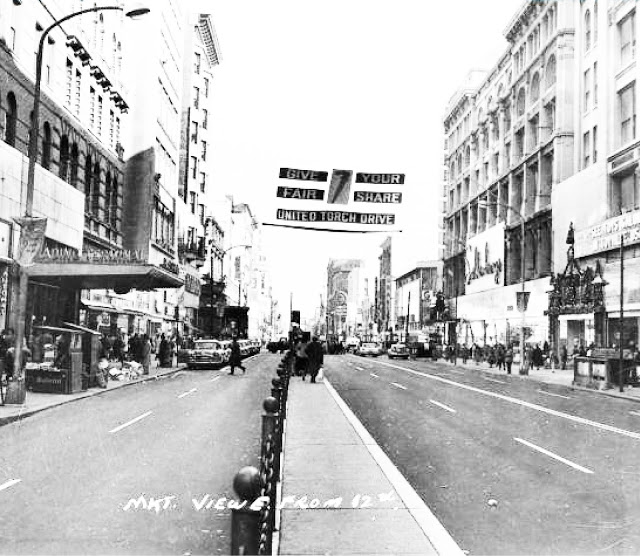

Philadelphia began to accommodate vehicular traffic after the turn of the 20th Century. This image, looking west from 12th Street, shows generous sidewalks for the burgeoning department stores, trolley tracks in the middle of the street, and a limited number of motor cars. The architecture is oriented to keeping pedestrians interested. (image credit: Center City District)

Early after the introduction of cars, streets were shared with horses and trolleys. This image of the headhouse of the Reading Railroad Terminal, looking east from 12th Street, shows generous sidewalks and a wide canopy at the entrance to the station, extending all the way to the curbline.

By the middle of the 20th Century, seeking greater capacity for automobile traffic, the City of Philadelphia narrowed the sidewalks of Market Street, and kept boarding islands for trolley riders (eventually, these trolleys were replaced by buses). In this image, again looking east from 12th Street, notice how the Reading Terminal canopy of over the sidewalk has also shrunken, as vehicular traffic is increasingly prioritized over pedestrian amenity. (image credit: Center City District)

This is the cross-section of the 1980s redesign of East Market Street, which remains to this day, but for some aesthetic changes in the 1990s. Sidewalks have been re-widened and transit islands have been eliminated, in favor of a curbside transit corridor and a center-running highway corridor. (image credit: Center City District)

Market Street today, looking east from 13th Street. Does this arrangement serve the transportation needs of today's Philadelphia? (photo credit: Jonas Maciunas)

Surging Pedestrian-Oriented Private Investment

Today, following some years of sluggish performance, there are new stores opening, noticeably more feet on the street, and there are big mixed-use projects rising and on the drawing board. There is more ongoing private investment than East Market Street has seen in decades. Developers predict that in five years, in addition to hundreds of new apartments, the larger format retail missing from Center City will all be here. The projects are fully leveraging the neighborhood’s transit accessibility and promoting themselves as walkable, urban developments. This is great news.

High quality pedestrian environments are the unifying theme of ongoing and planned development along the corridor. Does Market Street, itself, meet this goal?

A Dangerous Corridor for Pedestrians

But there is also a darker story here. East Market Street, from Independence Mall to City Hall, is the most dangerous pedestrian corridor of its length in Philadelphia; from 2008 to 2013, eighty-three pedestrians were struck by motorists. That’s only the incidents reported by the Philadelphia Police Department to PennDOT, and doesn’t even begin to account for the general level of discomfort experienced by pedestrians every single day. This sort of danger and anxiety is obviously bad for individual crash victims, but is also bad for retail trade. It undermines the development projects currently underway, and will keep the neighborhood from meeting its full economic potential.

(Quick aside: Sometimes, you'll hear that East Market Street has such high numbers of pedestrian crashes because there are so many more pedestrians (and cars) there than in other places. That's no excuse for accepting the problem. Center City creates vastly more economic activity than any other part of the Philadelphia or Pennsylvania... could you imagine if we discounted this economic productivity, just because Center City has more people and jobs than other areas? Of course not; that would be ridiculous.)

Proponents of VisionZero (coined in Sweden, adopted in New York City, and gaining steam in Philadelphia)say it’s time that we stop simply accepting this sort of vehicular violence as the cost of living or doing business in a major American city, and that we must shift our priorities. And make no mistake about it, public policy and street design shape transportation outcomes. By prioritizing people over their cars after an outcry about vehicular violence in the 1960s, Amsterdam has reduced traffic fatalities by 85% over the past several decades and, today, 38% of all trips in the city are made by bicycle.

This transformation has not come at the expense of quality of life or the success of the city's retail districts. To the contrary, central Amsterdam's pedestrian, transit, and bicycle-oriented streets are teeming with shoppers and the retail appears to be far more densely and widely distributed than in Philadelphia.

Shopping streets in Amsterdam are a joy to stroll and attract high quality tenants, no doubt because they generate high sales (translating into high rent for building owners). These enviable results are not just in spite, but in part because of the priority given to pedestrians, bicycles, and transit... other vehicular access is limited to deliveries (which have little if any alley access in many cases), much of which is handled in off-hours. (photo credit: Jonas Maciunas)

Hypothesis: taming vehicular traffic has actually improved the retailing environment in Amsterdam, and can do the same thing in American cities with the right supportive alternative infrastructure.

Reasons for Hope - infrastructure, preferences, and shifting behavior

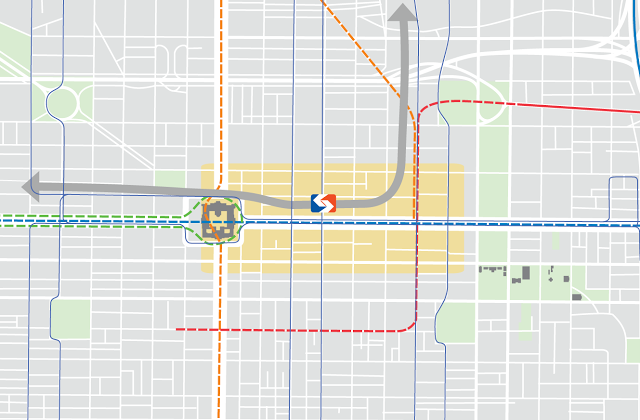

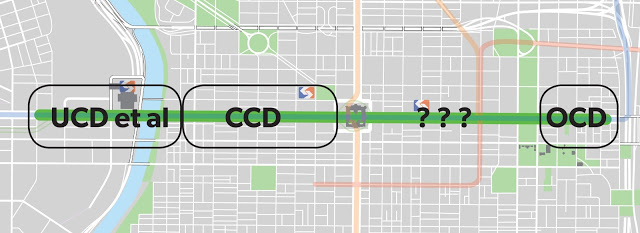

Fortunately, East Market Street is among the most transit-rich corridors in the country. Jefferson Station serves 26,500 daily Regional Rail trips. The Market-Frankford and Broad Street subways serve 187,000 and 123,000 daily trips, respectively. 38,000 people ride the PATCO each day. The trolleys handle 66,000 trips. SEPTA’s routes 33, 17, 23 (including the newly-split 45), and 47 are the all-day high-frequency routes serving the corridor, and they carry a combined 67,000 passengers each day. East Market is accessible to people without a car from all corners of the city and region; maybe priority should be placed not on accommodating individual motorists, but on facilitating deliveries.

East Market Street boasts unmatched transit access, ranging from Regional Rail, to three subways, subway-surface trolleys, and buses. Ridership on these modes dwarfs the number of motorists on Market Street. (graphic credit: Jonas Maciunas

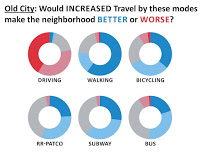

(graphic credit: Old City District + The RBA Group)

Just to the east,my firm is currently completing Vision2026, a planning framework for Old City. asking whether people think the neighborhood would get better or worse with more people traveling by various modes. Overwhelmingly, respondents of all groups expressed a belief that the neighborhood would get worse with more people driving, and better with more people walking, biking, and taking various modes of public transit.

Not only are preferences pronounced, but behavior also is already changing. According to DVRPC, the average daily traffic between Juniper and 8th Streets in 2013 was about 16,900 vehicles (certainly, many of them are just passing through), down from 23,700 in 1999. That decline of nearly 30% coincides with a 28% increase in SEPTA ridership and palpable surge in bicycling in the city. It goes beyond any recession-related blip and defies decades of conventional expectations by traffic engineers. A study by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission found that from 2010 to 2015, public parking inventory and occupancy have both fallen by 7% and 1.7%, respectively, even as Center City employment, dwelling, and visiting have surged. Something is changing.

Other Cities Have Shifted Priorities on Major Streets, and So Can Philly

If transit infrastructure, shifting preferences, and transportation trends are all pointing in a direction that supports a version of East Market Street that is safer for pedestrians and more welcoming to retail businesses, what does an alternative future look like? Consider New York City DOT’s removal of cars from transit-rich Times Square, and how successful that’s been. Fifty years ago, the Regional Plan Association suggested closing Broadway to traffic and got laughed out of the room, but by 2012 the idea’s time had come.

As Philadelphians, we're often tired of hearing about New York and the success of the pedestrianization of Broadway. Maybe we should step up to the plate and give ourselves something to brag about.

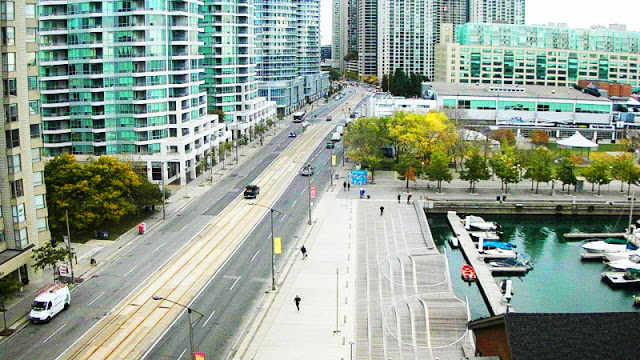

Toronto, a city also in the middle of a building boom, is boldly redesigning many important streets. Front Street, right in front of Union Station, has been rebuilt as a curbless “shared space” with a single travel lane in each direction, and now functions as a market square. Queens Quay, their waterfront boulevard and light rail corridor, has gone from a multilane highway with streetcars operating in mixed traffic, to a multimodal boulevard with dedicated tramways, a multi-use trail, generous pedestrian promenade, and a single travel lane in each direction. Boldest of all, the city is next planning to redesign King Street, and analog to our own East Market Street. The city’s planning director says that revisioning will include transit priority, dedicated bicycle paths, ample seating for shoppers, and possibly just a single vehicular lane, alternating directions from block-to-block, just to provide access, not space for through traffic.

Front Street, the threshold to Toronto's Union Station, was recently a multi-lane boulevard, divided by a planted median.

Front Street has been redesigned as a curbless "shared space," with only a single vehicular lane in each direction, transforming this critical gateway into a hub of community. Shouldn't Market Street provide a similar experience for Jefferson Station?

Queens Quay had been a classic multi-lane waterfront boulevard, with limited pedestrian and bicycle amenity, and streetcars frequently slowed down by motorists using their lanes.

Queens Quay was re-imagined as a true multi-modal corridor, complete with a multi-use trail, dedicated streetcar lanes, and a generous pedestrian promenade (rendering credit: Spine 3D)

The new Queens Quay opened in 2015. Without the luxury of extra right-or-way to claim, these improvements to the capacity of the street and the quality of the experience came at the expense of vehicular capacity and level of service. (photo credit: Connie Tsang)

Next: Toronto, with the help of Jan Gehl, will be tackling King Street. The street has a similar cross-section and economic purpose as Market Street. Shouldn't Philadelphia similarly confront the challenges facing Market Street?

Progressive Ideas, to the the East and West

Locally, sections of Market Street are already being reimagined to the east and west. On the other side of City Hall, protected bike lanes, advocated for by Bicycle Coalition and the Center City District and designed by Parsons Brinckerhoff and Studio Bryan Haynes, would take advantage of excessive roadway and provide space for safe cycling. On far East Market Street, Vision2026 is recommending the transformation of the 200 block of Market Street into a curbless, shared-space station plaza for the subway, complete with parking-protected bike lanes, enhanced transit shelters, and slow travel lanes. Neither of these are necessarily right for East Market, but the question becomes - between Old City and Market West, will we take a fresh look at how Philadelphia’s Main Street functions?

Old City Vision2026 recommends repurposing the 200 block of Market Street as a shared-space station plaza for the busy Market-Frankford subway. By eliminating vertical curbs in favor of more subtle material changes (stone, high-aggregate concrete) and removing traffic signals from intersections at 2nd and 3rd Streets, the street can empower pedestrians, accommodate more fluid (but slower) traffic, provide bicycle paths, and create the opportunity for occasional street festivals and bazaars. (rendering credit: Old City District and The RBA Group)

West of 3rd Street, Old City Vision2026 recommends maintaining the cross-section recommended in the 200 block, but not necessarily continuing the curbless, shared-space material treatment. By doing so, the street can provide protected bike lanes, higher amenity transit stops that don't block the sidewalk, on-street parking (principally for loading), a single travel lane and a turn lane as needed. This cross-section can continue west to 5th Street, and may need to change west of Independence Mall to accommodate the unique conditions of those blocks. (rendering credit: Old City District and Atkin Olshin Schade Architects)

The 30th Street Station District Plan recommends protected bike lanes on Market Street, among other dramatic improvements to the public realm. West of City Hall, various parties are working to implement the protected lanes that have been designed. In Old City, Vision2026 proposes a shared-space station plaza on the 200 Block of Market Street. Beyond coordination of an aesthetic update to furnishings and paving materials on East Market Street, will we make sure the city's resurgent shopping district lives up to its potential? (graphic credit: Jonas Maciunas)

Take the Opportunity, or Watch the World Pass You By

Market Street has evolved over the generations to meet the technology, trends, and preferences of its time. In the 1860s, it was largely unpaved, carried the Pennsylvania Railroad, and included market sheds at its center. Now as then, change is hard, and requires funding, trade-offs among multiple priorities, and creative design solutions. But could you imagine if, through the 20th Century, we had not risen to that challenge and kept a roadway designed for an obsolete 19th Century transportation system?

East Market Street was designed in 1984 and no longer serves the needs of our city or the preferences of the market. Not only does it create an unsafe pedestrian environment, constraining the economic potential of the district, but it provides no enduring pleasure. Philadelphia’s “main street” should be a joy to stroll along. Amid the ongoing surge of private investment, the time has come to take a hard look at the priorities of the public realm on East Market Street.

As a closing aside... there are many possible future configurations for East Market Street, prioritizing different combinations of modes in a variety of ways. Furthermore, different sections of Market Street - Old City, the core of East Market between Independence Mall and City Hall, and west Market Street - will each require their own treatments because of their unique needs (though continuity and connectivity between them is critical for certain purposes). At this point, however, more than proposing specific interventions or solutions, it is important to build consensus in identifying the problems that exist, and the need to address them around new priorities.

Specific proposals this early in the game, while important for the creative process, only provide talking points and boogey men for potential detractors, ultimately perpetuating the status quo. Work hard to assert the right values and priorities, casting a broad enough net to address interconnected issues, and the right design will present itself. That's not easy, or as immediately satisfying, but worth it in the long run. With dedication to safer streets, more productive real estate, and just a little luck, Philadelphia will get the chance to consider a series of alternative futures for East Market Street.