Back in last September, SEPTA was facing the very real prospect of drastic cuts in service because of decades of deferred maintenance resulting from a funding structure that gives it far less juice than other comparable systems. I called it the unnecessary doomsday scenario, but boy, what a doomsday scenario it would have been.

Since then, however, the passage of Act 89 by the Pennsylvania legislature, in the words of the General Manager, "is a watershed moment for transportation in the Commonwealth. For the very first time, transportation agencies have a predictable, bondable, and inflation-indexed funding solution to to repair failing bridges, highways, and transit systems across the state. Already, credit rating agencies foresee a positive economic outlook. The entire state stands to benefit from this landmark piece of legislation.

"For SEPTA, Act 89 provides an opportunity to play catch up on a growing $5 billion backlog of capital replacement needs. The funding will allow SEPTA to advance a wide-ranging program of mission critical projects, such as bridge replacements, substation overhauls, and and the customer experience."

What does all that mean? Basically, in addition to improved customer service, other management practices, and the long-awaited deployment of new payment technology, there will be a lot going on behind the scenes (and under the bridges) to get the existing system up to snuff and still functioning ten years from now. In other words, $5B for critical things that will, in many ways, go unnoticed and, unfortunately, might not be broadly appreciated.

One exception is going to be the replacement of the 1980 trolley fleet with new, low-floor boarding, higher capacity vehicles. THIS will be a transformative investment, especially for West Philadelphia, where what basically operates as a system of buses that can't get out of the way of an obstruction in the street, will be transformed into a modernized system that functions more like the light rail we're always finding ourselves jealous of in far-flung places like Portland and Houston. Faster boarding, greater vehicle capacity, and stations that extend the sidewalk out to the track will be like a brand new rapid transit system for West Philadelphia. This a big deal, and with a little luck (though limited confidence, given the recent track record), SEPTA will avoid the siren song of advertising/sponsorship, and develop/keep a strong visual brand for the newly improved system... but more on that another time.

But this all still begs the question: what's next? SEPTA has a predictable revenue stream in place for the first time ever. It's prudent to make these state-of-good repair and service improvements first, but before long, they will have been made, and we'll still have this revenue stream in place. We shouldn't be proposing any major service expansions until the system is restored, but once it is, the legislature could easily cut that funding stream if additional transportation needs of the region aren't being planned to be met.

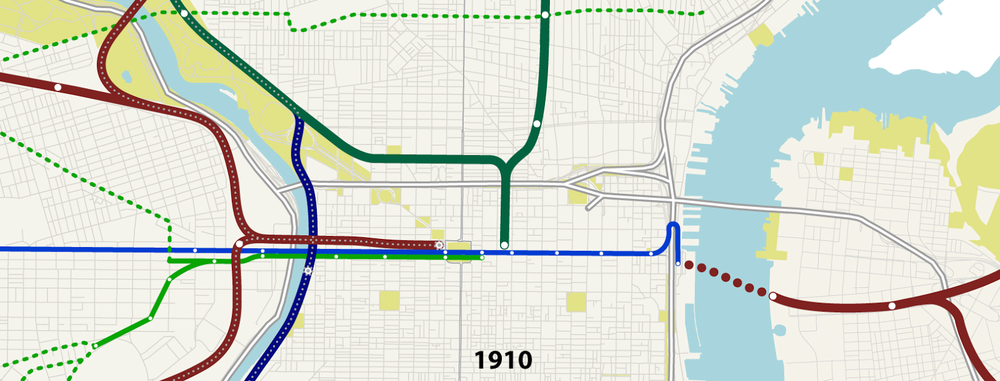

There will be plenty of time to speculate about service expansions - new subways, regional rail re-extension to places like Reading and Lancaster, trolley restoration, rapid transit on the Boulevard, and more. But right now, I thought it'd be good to illustrate the building of the Center City passenger rail network over the years. After all, it was built incrementally, not over night, and any future changes should stand on the shoulders of the evolution of the system before them. These maps are based on a my synthesis of historic maps of the city and some cursory, non-academic research (wikipedia and some rail fan sites) on operators and stations. Other than the ones that still exist today, I avoided showing trolleys (which is a whole 'nother discussion of disinvestment, repeated city after city). This is not meant to be an exhaustive review of each and every detail, and I'm sure there are corrections to make, but the intent is to show the general trajectory we have been on, in order to better consider where we'll go next.

In the earliest days, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran trains all the way down Market Street to the Delaware River by way of Dock Street. But after we realized you really shouldn't be running steam locomotives down you Main Street, here is what we got. The Reading Railroad, naturally, terminated at Reading Terminal and the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated at the grand Broad Street Station, both built in 1893. It's worth noting that until 30th Street Station was built, and Broad Street was demolished, intercity trains (think today's Amtrak service) would pull all the way into Broad Street, across the street from city hall, and then back out to continue their journey.

There was no subway or 30th Street Station, just a smaller station at 32nd Street. The Baltimore and Ohio ran a line along the Schuylkill, with a pretty beautiful station at Chestnut Street, and service to New York City that didn't require the Broad Street back-in-and-out. West Philadelphia trolleys converged on Market Street and ran all the way to Front Street, where they looped around. The Pennsylvania Railroad also ran a New Jersey based division that terminated at Camden (these trains went north and to the shore). Ferry service between the cities abounded. Remember, unlike today's Monolithic SEPTA (with the exception of PATCO and NJTransit buses) this is in the era when services were run by lots of different operators. I won't be getting into the details of which is which, generally, but it's worth remembering.

As you can imagine, trolleys on Market street got more and more crowded. Long story short, the trolleys were put in a tunnel, terminated at City Hall (just like today) and a company was created, authorized by the City, to build a Market Street subway in 1907. Originally, this it was elevated west of 22nd Street and terminated at the Delaware, connecting passengers to the Ferries from Camden. It was called the Ferry Line, and would soon extend to South Street, where there was another ferry terminal. It's also worth noting that in the days before the Broad Street subway, there were more stops on the inner section of the Reading line, including at Fairmount and Girard Avenues.

The 1920s and 30s witnessed huge expansion of the system. Let's look at what those expansions were.

With the construction of highways sweeping the nation, you wouldn't think there would be much happening on the railroad front. In fact, retrenchment was the spirit of the era.

Despite Ed Bacon's fantasies of miniature trolleys shuttling people back and forth on Chestnut Street, the 1960s were still all about highway construction. However, this period also witnessed the implosion of the private passenger railroads. Everything got really confusing and entities like SEPTA were created to manage the chaos. In 1968, PATCO began running one the three lines PB had recommended into Center City by way of the Ben Franklin Bridge. Though SEPTA didn't own track and rolling stock until 1983, by 1966, both the Reading and Pennsylvania Railroads operated commuter lines under contract to the Authority. This set up the situation where the SEPTA regional rail system was bifurcated between trains terminating at Suburban and those terminating at Reading. Enter: Vukan Vuchic.

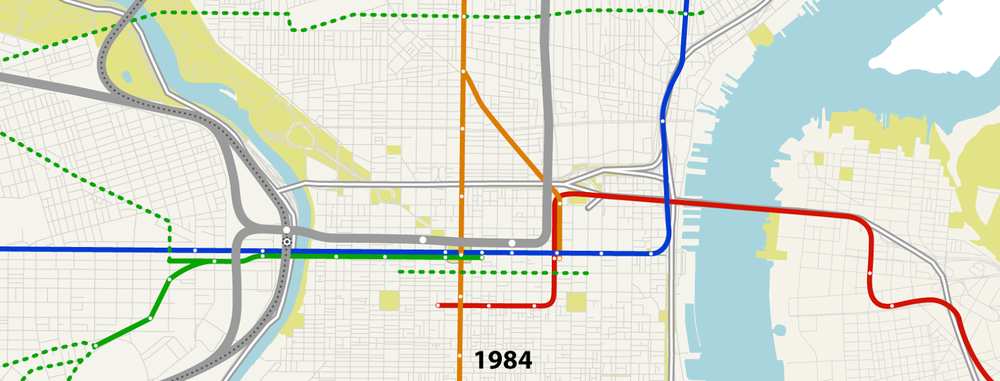

The construction of I-95 on the Delaware River shifted the El from Front Street into the highway alignment we know today, and replaced a Fairmount station with today's Spring Garden Station. Ed Bacon's vision for Chestnut Street was tranformed into The Transitway in 1976, though it would be incrementally dismantled. Most importantly, the Center City Commuter Connection created a tunnel between Suburban Station and Reading Terminal, renamed Market East (and now, Jefferson Station). This connection allowed for trains that used to terminate at each station to pass through Center City to become another route on the other side. Though SEPTA has been criticized for not sufficiently taking advantage of the connectivity the tunnel allows, as I've discussed before, doubling the transit access to Market West is indelibly linked to its growth as an office district.

Since the Tunnel's completion in 1984, however, little has changed in the system, with the exception of the creation of the River Line between Camden and Trenton on the other side of the Delaware. In Philadelphia, the broader retrenchment trend of the second half of the 20th century continued with the gradual elimination of the Chestnut Street Transitway and the 1992 replacement of Route 23, 15, and 57 trolleys with buses (though the 15 on Girard Avenue would be re-instated in the next decade).

It's been a long time since any major network changes have happened in the central Philadelphia transit system, mostly because SEPTA has been doing its best just to minimize the bleeding. But now that the Authority is in a strong financial position for the foreseeable future and is making lots of state-of-good-repair improvements (and majorly re-investing in the existing trolley system), the question should be asked: what's next?

There will be plenty of time to thinking and discuss that, but a good place to start is to look at where we've been.

Since then, however, the passage of Act 89 by the Pennsylvania legislature, in the words of the General Manager, "is a watershed moment for transportation in the Commonwealth. For the very first time, transportation agencies have a predictable, bondable, and inflation-indexed funding solution to to repair failing bridges, highways, and transit systems across the state. Already, credit rating agencies foresee a positive economic outlook. The entire state stands to benefit from this landmark piece of legislation.

"For SEPTA, Act 89 provides an opportunity to play catch up on a growing $5 billion backlog of capital replacement needs. The funding will allow SEPTA to advance a wide-ranging program of mission critical projects, such as bridge replacements, substation overhauls, and and the customer experience."

What does all that mean? Basically, in addition to improved customer service, other management practices, and the long-awaited deployment of new payment technology, there will be a lot going on behind the scenes (and under the bridges) to get the existing system up to snuff and still functioning ten years from now. In other words, $5B for critical things that will, in many ways, go unnoticed and, unfortunately, might not be broadly appreciated.

One exception is going to be the replacement of the 1980 trolley fleet with new, low-floor boarding, higher capacity vehicles. THIS will be a transformative investment, especially for West Philadelphia, where what basically operates as a system of buses that can't get out of the way of an obstruction in the street, will be transformed into a modernized system that functions more like the light rail we're always finding ourselves jealous of in far-flung places like Portland and Houston. Faster boarding, greater vehicle capacity, and stations that extend the sidewalk out to the track will be like a brand new rapid transit system for West Philadelphia. This a big deal, and with a little luck (though limited confidence, given the recent track record), SEPTA will avoid the siren song of advertising/sponsorship, and develop/keep a strong visual brand for the newly improved system... but more on that another time.

But this all still begs the question: what's next? SEPTA has a predictable revenue stream in place for the first time ever. It's prudent to make these state-of-good repair and service improvements first, but before long, they will have been made, and we'll still have this revenue stream in place. We shouldn't be proposing any major service expansions until the system is restored, but once it is, the legislature could easily cut that funding stream if additional transportation needs of the region aren't being planned to be met.

There will be plenty of time to speculate about service expansions - new subways, regional rail re-extension to places like Reading and Lancaster, trolley restoration, rapid transit on the Boulevard, and more. But right now, I thought it'd be good to illustrate the building of the Center City passenger rail network over the years. After all, it was built incrementally, not over night, and any future changes should stand on the shoulders of the evolution of the system before them. These maps are based on a my synthesis of historic maps of the city and some cursory, non-academic research (wikipedia and some rail fan sites) on operators and stations. Other than the ones that still exist today, I avoided showing trolleys (which is a whole 'nother discussion of disinvestment, repeated city after city). This is not meant to be an exhaustive review of each and every detail, and I'm sure there are corrections to make, but the intent is to show the general trajectory we have been on, in order to better consider where we'll go next.

The Early System

In the earliest days, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran trains all the way down Market Street to the Delaware River by way of Dock Street. But after we realized you really shouldn't be running steam locomotives down you Main Street, here is what we got. The Reading Railroad, naturally, terminated at Reading Terminal and the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated at the grand Broad Street Station, both built in 1893. It's worth noting that until 30th Street Station was built, and Broad Street was demolished, intercity trains (think today's Amtrak service) would pull all the way into Broad Street, across the street from city hall, and then back out to continue their journey.

There was no subway or 30th Street Station, just a smaller station at 32nd Street. The Baltimore and Ohio ran a line along the Schuylkill, with a pretty beautiful station at Chestnut Street, and service to New York City that didn't require the Broad Street back-in-and-out. West Philadelphia trolleys converged on Market Street and ran all the way to Front Street, where they looped around. The Pennsylvania Railroad also ran a New Jersey based division that terminated at Camden (these trains went north and to the shore). Ferry service between the cities abounded. Remember, unlike today's Monolithic SEPTA (with the exception of PATCO and NJTransit buses) this is in the era when services were run by lots of different operators. I won't be getting into the details of which is which, generally, but it's worth remembering.

Subways on Market Street

Rapid Expansion

The 1920s and 30s witnessed huge expansion of the system. Let's look at what those expansions were.

- The Frankford line opened in 1922. For a brief period, the Market Street subway would have two branches - the Ferry and Frankford lines.

- The Broad Street line opened in 1928, but terminated at Lombard/South.

- In 1932, the Broad Ridge Spur began service from the north to 8th and Market Streets.

- The Pennsylvania Railroad opened Suburban Station in 1930 and 30th Street Station in 1933, intending to send intercity trains through 30th Street and suburban ones underground (I do love the station's double-meaning) through Suburban. The Broad Street Station remained, however, presumably because money had run out to tear it down, and continued to serve a portion of the city's intercity service until it was torn down in 1952.

- in 1936 (yes, i know, a year after the image is labeled), the Delaware River Joint Commission (predecessor to PATCO) began running the "Bridge Line" on the newly constructed Ben Franklin Bridge. This would spell trouble for the ferries. Originally, this line only ran between Broadway in Camden and 8th and Market Streets in Philadelphia. Connections to the Pennsylvania Railroad were required for any journeys east of Camden from Philadelphia.

Mid-Century Retrenchment

With the construction of highways sweeping the nation, you wouldn't think there would be much happening on the railroad front. In fact, retrenchment was the spirit of the era.

- In 1952, the Pennsylvania Railroad demolished Broad Street Station, formalizing the condition we know today (with one major exception) where regional trains run to suburban, and intercity trains run to 30th Street.

- The B&O Station at 24th and Chestnut was closed in 1958.

- After a some temporary closure, the Ferry Line of the Market Street subway was closed in 1953. This eventually makes way for Delaware Avenue and I-95.

- There is a general demise of regular ferry service across the Delaware,

- The Broad Street line had been extended south of Lombard/South to Snyder Avenue in 1938.

- Most notably, the Delaware River Port Authority was created in 1951, taking over the Bridge Line. Hired by the Authority to develop a rapid transit plan for South Jersey, Parsons Brinckerhoff recommended building a tunnel to serve three lines. Though the tunnel was deemed to expensive and eastern improvements wouldn't happen yet, the line was extended in Philadelphia to the Locusts Street terminus we know today.

More Stagnation, but stabilization in a Chaotic Era

Despite Ed Bacon's fantasies of miniature trolleys shuttling people back and forth on Chestnut Street, the 1960s were still all about highway construction. However, this period also witnessed the implosion of the private passenger railroads. Everything got really confusing and entities like SEPTA were created to manage the chaos. In 1968, PATCO began running one the three lines PB had recommended into Center City by way of the Ben Franklin Bridge. Though SEPTA didn't own track and rolling stock until 1983, by 1966, both the Reading and Pennsylvania Railroads operated commuter lines under contract to the Authority. This set up the situation where the SEPTA regional rail system was bifurcated between trains terminating at Suburban and those terminating at Reading. Enter: Vukan Vuchic.

A Breakthrough Moment

The construction of I-95 on the Delaware River shifted the El from Front Street into the highway alignment we know today, and replaced a Fairmount station with today's Spring Garden Station. Ed Bacon's vision for Chestnut Street was tranformed into The Transitway in 1976, though it would be incrementally dismantled. Most importantly, the Center City Commuter Connection created a tunnel between Suburban Station and Reading Terminal, renamed Market East (and now, Jefferson Station). This connection allowed for trains that used to terminate at each station to pass through Center City to become another route on the other side. Though SEPTA has been criticized for not sufficiently taking advantage of the connectivity the tunnel allows, as I've discussed before, doubling the transit access to Market West is indelibly linked to its growth as an office district.

Today - The Lull Before the What?

Since the Tunnel's completion in 1984, however, little has changed in the system, with the exception of the creation of the River Line between Camden and Trenton on the other side of the Delaware. In Philadelphia, the broader retrenchment trend of the second half of the 20th century continued with the gradual elimination of the Chestnut Street Transitway and the 1992 replacement of Route 23, 15, and 57 trolleys with buses (though the 15 on Girard Avenue would be re-instated in the next decade).

It's been a long time since any major network changes have happened in the central Philadelphia transit system, mostly because SEPTA has been doing its best just to minimize the bleeding. But now that the Authority is in a strong financial position for the foreseeable future and is making lots of state-of-good-repair improvements (and majorly re-investing in the existing trolley system), the question should be asked: what's next?

There will be plenty of time to thinking and discuss that, but a good place to start is to look at where we've been.