Philadelphia has a beautiful history and network of parks and trails. After a long hike a little while ago, it dawned on me that parks and trails, just like buildings and streets, range from urban to rural, and that "getting it right" in those various contexts makes a huge difference. In other words, beaux-arts fountains in the woods make about as little sense as building a raised ranch with a picket fence next to City Hall. I'm going to use this post to show how a great long hike through Philadelphia parkland exposes you to a nearly perfect transition through the trail transect.

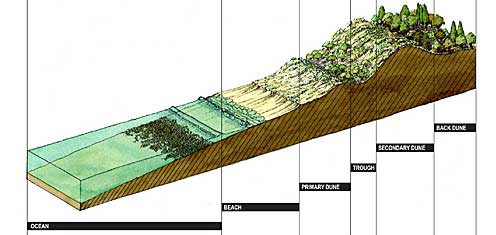

But first - quick primer on New Urbanism and transect theory. The idea arose by following the lead of biologists and ecologists who recognized that life thrives in a variety of environments because of different symbiotic relationships within those environments. The diagram of the natural transect looks something like this:

(Center for Applied Transect Studies)

Translating the Language of Natural Ecosystems to the Built Environment

(James Wassell)

When it comes to the human environment, we've realized that traditional settlement patterns come with great variety, but just like the natural environment transitions from coastline to woodlands, they range from rural to urban. Not only is it difficult to transfer elements between zones (i.e., shrimp would die on mountaintops), but the various zones also symbiotically reinforce each other (wetlands or grassy dunes protect inland ecosystems from erosion by the ocean). So... a skyscraper on the prairie is ridiculous (and probably not worth the construction cost), in the same way that a farm (as opposed to a community garden) in a rowhouse neighborhood can do more harm than good. The theory goes that the limiting factor of organically powered movement (walking, bicycling, occasional horse-riding) facilitated this recognizable pattern of organization, and that the advent and promulgation of the automobile allowed for all sorts of seemingly liberating, but previously utterly unrecognizable forms (100s of acres of homogeneous housing pods, spaceship office parks, and parking lagoon shopping centers). Zoning codes and real estate financing soon followed these new forms.

(DPZ)

Twenty years ago or so, looking for an alternative to the unending sprawl, planners realized they could create development codes that reflect those traditional walkable patterns, ranging from rural to urban, depending on what markets would allow and what communities saw for themselves. The firm of Duany Plater-Zyberk developed the

and a diagram demonstrating the rural to urban transition of human settlement. Development needn't also sequentially follow this transition (there's plenty a lovely tight-knit Italian hillside town that butts right up against farmland), but knowing whether you're trying to create a rural place, an urban place, or something in between is really important for avoiding dissonance.

The Transect of Philadelphia's Fairmount Park

Just as with other elements of the human environment, parkland and trails can also follow a transect. Coming back to where I began this post... after recently taking the train out to Chestnut Hill, it struck me that the route we took nearly perfectly embodied that rural to urban transition. Let me now take you on that tour.

Approaching Forbidden Drive

SEPTA's regional rail drops you twelve miles from Center City, still a stone's throw from the edge of the Fairmount Park System.

Chestnut Hill is a town straight out of a Harry Potter novel, complete with a Belgian block main street, Germantown Avenue, with trolley tracks and retail buildings made of stone and wood.

Thickly wooded residential streets link Germantown Avenue to the edge of the woods.

Trails leading to Forbidden Drive feature limited paving, no landscaping or fencing, and are really just a cut through the woods meant for hikers, mountain bicyclists, and the occasional equestrian.

Forbidden Drive (named for the forbidding of automobiles in the 1920s)

Gravel trail in the woods, running along the Wissahickon Creek, rustic wood rail fencing, no landscaping to speak of at the edge of the trail. Generally, only Parks and Recreation or Police vehicles are permitted.

An 18th Century Inn still draws a crowd, without much modern infrastructure

Lincoln Drive

Still running alonng the Wissahickon, now across the creek from traffic on Lincoln Drive. Asphalt paving introduced, mowed lawn, but little other landscaping... roadways pass far overhead

Kelly Drive

As the Wissahickon joins the Schuylkill River the trail runs alongside a roadway (Kelly Drive) for the first time. Evenly spaced sycamores and a low wall of irregularly shaped stones.

Introduction of trail lamps, a parallel gravel path, pastoral settings to view Center City for the first time

Monumental plazas, fountains, and public art.

At Boathouse Row, curbs are introduced, benches are increased, and the trail is widened with brick edge treatments

The Art Museum

After moving away from the Schuylkill after Boathouse Row at the Water Works, Beaux Arts buildings begin to appear over the manicured lawn, regularly spaced lamps, and an allée of trees

Approaching the Art Museum steps, crowds increase

The trail opens up to a full public plaza at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, one of the city's greatest public monuments

Benjamin Franklin Parkway

From the top of the Art Museum Steps the same place where a reservoir once provided water for the city below, its plaza, Eakins Oval, and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway visually link Fairmount Park and the Art Museum to the heart of Center City.